To commemorate the 20th anniversary of implementation of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, we are featuring stories of those who in 1997 campaigned against the repeal of the law adopted by Oregon voters 3 years before. Today we are featuring Geoff Sugerman, who managed the Measure 16 campaign for the Oregon Right to Die Political Action Committee; served as the communications director for the 1997 No on 51 campaign; and continues to work as a political strategist with Death with Dignity National Center.

Other installments in the series:

- 20 Years of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act

- “A Better Way”: George Eighmey’s Journey Toward Death with Dignity Nationwide

- From the Archives, 1997: In Letters to Lawmakers, Oregonians Voice Support for Death with Dignity

- “A Last Loving Gift”: Nora Miller on Grief, Advocacy, and the Right to a Dignified Death

- “Everyone Should Have This Option”: Jan Rowe on her Family’s Commitment to Death with Dignity”

- “We Have to Be Part of the Debate:” Ann Jackson on the Role of Hospice in the Death with Dignity Movement

- “What Brittany Asked Us to Do”: Deborah Ziegler’s Advocacy for Death with Dignity Honors a Promise to Her Daughter

*

The movement to bring Death with Dignity to Oregon was started and guided by a small group of seasoned attorneys, business people, and healthcare professionals. To hear Geoff Sugerman tell it the 1994 campaign to pass Measure 16, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, was by far the most difficult and important work of his 30-year political career.

Starting from Scratch, Building on Initial Success

“We really started from less than Square One,” says Geoff, who managed the Measure 16 campaign for the Oregon Right to Die Political Action Committee and served as the communications director for the 1997 No on 51 campaign. Drafted and placed on the ballot by the Oregon State Legislature, Measure 51 sought to repeal the nation’s first assisted-dying law.

Led by Eli Stutsman, Elvin “Al” Sinnard, and a small group of committed Oregonians, the campaign was seeking a manager in 1993. Sugerman applied, and despite his lack of experience in ballot measure campaigns, he was selected to work with Stutsman and the steering committee to direct the campaign’s day to day activities.

From collecting 125,000 signatures in less than ten weeks and fighting constant media battles with The Oregonian to building a fundraising operation and creating a sophisticated series of print and television advertisements, Stutsman and Sugerman knew the campaign would be close.

“We were outspent $5 million to $1 million in the 1994 campaign, the most that had ever been spent against a ballot initiative campaign at that time,” Sugerman recalls.

But the groundswell of grassroots support for Death with Dignity, combined with the carefully honed messaging and media strategy crafted by the campaign team led voters to approve Measure 16 on November 8, 1994 by a margin of 51.31% to 48.69%.

In 1997, the Death with Dignity law was placed back on the ballot by the Oregon State Legislature. Measure 51 sought to repeal the nation’s first assisted-dying law, three years after voters approved the original law.

The groundwork they laid in 1994, and the lessons they learned along the way, made it far easier to conduct outreach, raise funds, and develop a messaging and media strategy to counter the formidable opposition from state politicians, medical associations, and the Catholic Church.

“We were able to draw on our work from the Measure 16 campaign to build a campaign structure and a donor structure and a media structure” for the 1997 effort, Geoff says.

Campaign to Pass Oregon Death with Dignity Act: A Collaborative Effort

Geoff Sugerman (left) with Eli Stutsman, JD, leader of the Oregon Right to Die PAC and lead author of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act.

Sugerman worked closely with Oregon Right to Die founder Eli Stutsman, JD, who led the Measure 16 campaign and subsequently founded the Oregon Death with Dignity Legal Defense and Education Center (ODLDEC) to defend the law from a legal challenge brought by National Right to Life just weeks after Measure 16’s passage.

The PAC and ODLDEC worked in tandem. Critical to these efforts were the late John Duncan, the first executive director of ODLDEC, and the late Steve Telfer, who served on the Death with Dignity National Center Board of Directors for a decade to 2016. Both were integral members of the effort to defend the law.

In 1994, one of the challenges was to craft a message that convinced voters the proposed law had numerous safeguards to protect patients from possible coercion and harm by doctors.

Another was to convince voters through the stories of terminally ill Oregonians that physician assisted death was a vital option to prevent needless suffering at the end of life.

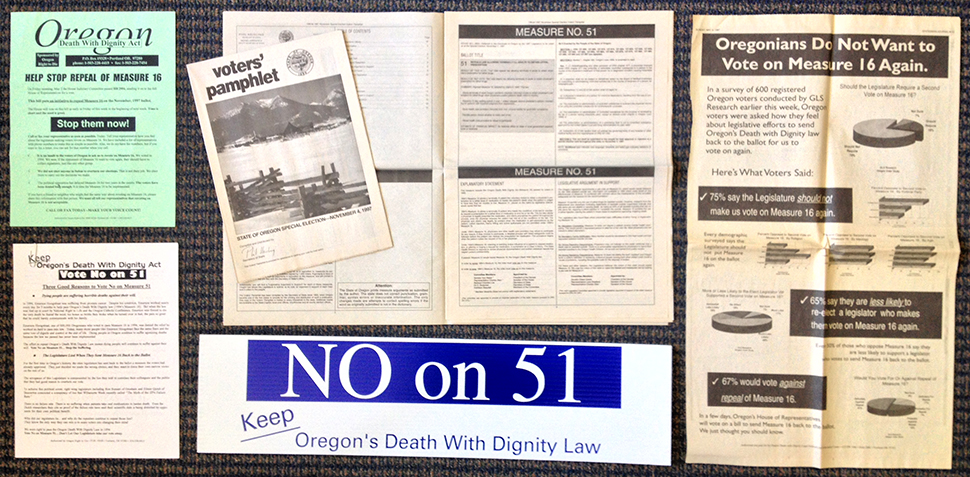

No on 51 campaign materials.

Finding a way to transcend the contentious ideological and faith-based arguments against the law and appeal to voters’ basic humanity was a formidable task. But Sugerman and his colleagues found that, as with most political campaigns, putting a human face on a complex policy issue was a highly effective means of connecting with voters.

“Our campaign was very patient- and people-centric,” Geoff says. “But it was also very much based on the polling data and what we felt based on research were the most effective messages and the most compelling messengers.”

Patients, many of whom reached out to Oregon Right to Die and volunteered their time to its efforts, “were the backbone the 1994 campaign. They inspired us. They worked incredibly hard on the campaign. And they were willing to share their most personal stories with voters,” said Sugerman.

Medical professionals also served as key spokespeople for both Measure 16 and Measure 51. Portland physician Dr. Peter Goodwin, who died in 2012, was an outspoken advocate for assisted dying and worked diligently to bring other physicians on board, and to convince the Oregon Medical Association to stay neutral on the 1994 campaign. Oregon Right to Die also recruited Barbara Coombs Lee, a nurse and a chief petitioner for the Act who would later found Compassion & Choices.

“We knew nurses were the most trusted people in the medical profession,” Geoff says. “Everything we did was very well tested through research.”

California-based advertising and marketing firm Zimmerman & Markman helped to create media pieces and television ads for both the Measure 16 and No on 51 campaigns. Their expertise and the on-the-ground strategy developed by the leaders of the PAC led to the creation of a compelling and highly persuasive media campaign.

The 1994 effort also relied heavily on grassroots organizing–phone banks, direct mail solicitations, signature gathering–and the contributions of a large network of volunteers. Geoff reflects fondly on the many individuals, and one in particular, who devoted countless unpaid hours to advancing the cause of Death with Dignity.

“One of the most amazing people in that whole campaign was Emerson Hoogstraat,” a retired finance professor at Portland State University. “During the 1994 campaign, he literally came into the office almost every day to process mail for us,” even as he was suffering from cancer that had spread from his prostate to his bones.

Hoogstraat died in March of 1995, while the fate of the law was still being debated in the Ninth Circuit Court.

“He was unable to use the law in the end,” Geoff says. ”It was a terribly sad thing. But it was people like him that made our campaign a success. There were so many other people who were instrumental to the campaign. People like Margaret Grossweiler, former State Rep. Carolyn Tomei and Kristin Reese, who was our office manager. It was their work and their support that really pushed us over the top.”

Back to the Ballot Box in 1997

In early 1997, the Oregon State Legislature was embroiled in a heated debate over the fate of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. Stutsman, Sugerman, Telfer and other members of the PAC and the Center “were really actively involved in the legislative process, trying to get the legislature to not send that law back to the ballot.”

They worked with then Oregon State Representative and current Death with Dignity National Center Board Chair George Eighmey to block opponents on both sides of the aisle. Nevertheless, legislators succeeded in placing Measure 51 back on the November, 1997 ballot.

The Death with Dignity team was frustrated but undeterred. Their early polling demonstrated what they knew intuitively: Oregonians would not take kindly to being asked to vote on an issue when they had unequivocally made their preference known.

“People in Oregon—and I think this is true still today—really honor that system of being able to vote on issues and decide issues themselves,” Geoff says. “When they decide them, they decide them. They don’t want anyone second-guessing them.”

Stutsman, Sugerman and the team from Zimmerman & Markman used these findings to develop a simple yet highly effective message.

“Respect the Will of the People”

“It was the ‘will of the voters’ message that carried the day time and time again,” Geoff says. “‘Didn’t you hear us the first time? Why are you making us do this again?’”

The prevalence of this sentiment, and its distance from the fraught moral, ethical, and religious debates that characterized the Measure 16 battle, made for a far easier campaign.

“We realized that not only did we have that core of voters who voted for Measure 16 initially, but we had another group of voters who had voted against the law who didn’t think it should come back to them again,” Geoff says. “That was a critical piece of our success and why we won by such a greater margin in ’97 than we did in ’94.”

Another key factor, in Sugerman’s opinion, was the ineffective messaging of the Yes on 51 camp, led by opponents in the state legislature as well as the well-funded Catholic lobby.

“‘It’s fatally flawed’ is the message that they started with in the Legislature,” Geoff says. “The “it” in question was Measure 16. But by using the message, ‘Yes on 51: it’s fatally flawed,’ “they were essentially campaigning against themselves. It was just poor messaging. It was confusing to voters, and when voters are confused they vote no.”

Yes on 51 campaign materials

Oregon Right to Die placed full-page ads in papers around the state, topped with boldface type that read, “Oregonians do not want to vote on Measure 16 again.”

With the support of a core group of donors recruited during the 1994 campaign, and a wealth of messaging experience from the 1994 campaign, and the leadership of Stutsman, “we were able to run a much more media-centric campaign in ’97,” Geoff says.

They also did battle with The Oregonian’s editorial board, countering the barrage of pro-51 op-eds and pushing back against articles they thought misrepresented the facts.

Geoff served as the main media contact for the No on 51 campaign. The work was intense; the pace, relentless. Fortunately, he had help.

“My dad (Bob Sugerman) was a huge supporter of the law,” Geoff shares. “In ’97, he came out for the last two and a half weeks of the campaign from Ohio to help us. I remember sitting one day with him in my office, where the phone is just constantly ringing, and he’s answering the phone, and finding out who the reporter is, and where they’re from, and what their deadline is, and writing it down, and I’m on the other phone, calling reporters back. He told me later it was one of the best times he ever had, especially when he got to talk to (Washington Post columnist) David Broder.”

When I finally had a chance to step back from it I felt like I had done what I was supposed to do in my life.

As in 1994, the best-funded and most vocal opposition came from the Catholic Church, which called on its membership to support Measure 51 and repeal the Oregon Death with Dignity Act.

“We had to out them as our opposition and we had to go straight on against the church hierarchy,” Geoff says. “We had plenty of polling data that seemed to suggest that there were a lot of members of the Catholic Church that supported us.”

The No on 51 team also took cues from the reproductive rights movement, which had been particularly effective at identifying “a clear division between the church hierarchy and members of the church. They seemed like they were losing touch with their constituents. And so we tried to use that as a wedge with those voters.”

In the end, Oregonians made their voices heard loud and clear. As predicted, 60% of voters cast their ballots against Measure 51. The media’s focus on the ballot initiative campaign was so narrow that reporters missed a crucial story: the court challenge against the Death with Dignity Act was dismissed, and the law went into effect just days before voters defeated the repeal effort.

Death with Dignity: It’s Personal

Geoff has remained committed to the cause of Death with Dignity. Twenty years after the No on 51 campaign, he continues to work with Death with Dignity National Center on national and state-specific campaign strategy. For him, his experience fighting for the right of all Americans to die with dignity was transformative.

“From a personal standpoint, it was by far the most important thing I ever did in my life,” Geoff says of the campaign for the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. “I remember when I finally had a chance to step back from it months later, I felt like I had done what I was supposed to do in my life. I still believe that today.

“That’s why we succeeded in the end. We never gave up on the belief that this was so important. And we never knew we were supposed to lose.”

He notes that the law started a national conversation about terminally ill patients’ quality of life that led to tangible improvements in end-of-life care.

“The fact that that today we take much better care of dying people than we ever did before is because of Oregon’s law,” Geoff says. “We saw the changes almost start immediately after the law passed. Even before it went into effect, you started seeing doctors saying, ‘I’ll treat your pain more aggressively.’ Not, ‘You can suffer through to the end of your life.’ And that’s the way it’s supposed to be.”

No comments.