By Joel Merchant

Our most influential teachers might be people we never meet, never sit in their class. We know them through books, oral history, stories. Yet, the same mystery of teacher-student relationship exists. As the saying goes, “when you’re ready, a teacher appears.” The function of good teachers is to help us see things in new ways.

One of my teachers is Dr. Sheldon Kopp who wrote If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, a book about the pilgrimage of psychotherapy patients. Wonderful because it was encouraging; perfect because I was in a time of frightful personal crisis. He writes, “Crises marked by anxiety, doubt, and despair…(are)…periods of personal unrest that occur at the times when a person is sufficiently unsettled to have an opportunity for personal growth.”

If we associate “learning” only with “school,” we risk missing how life’s pleasurable, unexpected, frightening, incomprehensible events enrich us with discoveries about who we are. A common experiences to a tragic event’s swirl of confusion, is feeling isolated. We know, intellectually, other people experience anxiety, doubt, despair, unrest—yet we still feel terribly alone during these storms.

A Life’s Journey

Think about our journey through life. Pack the steamer trunk. Double-check the maps. Set off in the direction we’re sure will get us where we want to go. Many carry a strong cultural bias toward individualism. Whatever happens, my father used to say, “I can handle it myself.” Then, tragedy strikes. We collide with an immovable object.

We’re not quick to talk about many of the most challenging experiences. A friend described his as “grueling, turbulent, breathless, helpless, shocked, trapped in a washing machine during the spin cycle, and hung out to dry.” After emotional turbulence, we rejoice at again feeling normal and healthy. And, yes, we also understand: we’re forever changed.

This story will become serious soon enough, so first, a lighter note. Picture this. Years ago, in growing dusk, walking a New York City sidewalk, my tall person’s legs taking long strides, turned slightly toward friends, more involved in animated college student conversation than wary of my path. I walked full tilt into a metal lamp post. It was a shattering hit along my body’s front center vertical line. Forward momentum stopped only after an arm and leg was draped around either side of the post. I crumpled straight down, losing consciousness. An unfamiliar, disconnected, observant part of me thought, “Oh. A ringing sound. The pole is hollow. That’s how a stringed instrument’s sound chamber works.”

“Now, We’re Changed”

Most of us are untrained for emergencies. Lacking experience, we’re unfamiliar and uncomfortable with tragedy—not others, not our own. It’s awkward when tragedy strikes a friend. We’re not sure how to be present. We keep our distance. We look on from a safe place. We read the paper: “Whew. What a relief this happened to someone else” (thinking, “This time”). We approach, confused by mixed feelings, perhaps guilt. “I cannot imagine…” Our voice trails off. It’s difficult to hide our hesitation that the person in pain could be us.

The journey through another person’s suffering is intimate. We look on, thinking that perhaps sympathy is appropriate, but helpless to express it. We imagine how we might feel in similar circumstances. Some fall into the trap of telling the person having the experience how she must feel. This doing so is less emotionally painful than asking “How are you doing?” That question crosses the psychological safety line, brings us closer to seeing, perhaps too clearly.

Having nothing to say provides little relief from the confusion and awkward silence that accompanies pain. A friend shares her experience:

Others consider that tragedy is private, that they are outsiders, not qualified to respond, especially since what you write or say is intimate. They listen to you, but fear their response would be (what?) judgmental? critical? Pain and sadness envelope a person who suffers a loss. Its protective function is to help us survive the experience. But it isolates us because it is difficult for others to see us as we are. People are absorbed in their own lives, and don’t feel the pain. Once, we were the same. Now, we’re changed.

Time Is Important

Time is important, not because “time heals” or “with time, you’ll get over it.” It’s only as time passes that we can know if the tragedy will do us in, or if we survive. A friend reminded me, “If this doesn’t kill me, it’ll make me stronger.” We understand ourselves in new ways. We cannot be the same. The experience becomes part of the story we tell that defines our life.

Why do we hesitate to tell our stories? Do we fear projecting our suffering on to the listener? “Why would anyone be interested?” “Who’d want to talk about that?” “My story doesn’t compare with the trouble she’s had.” Tragedy’s traveling companion is a sense of isolation. Everyone has a story to tell, but they’re difficult to share. Tragedy yawns open before us, a chasm, with no apparent way around or over. Crossing requires the leap of faith. If we share our story, others will listen. Someone else cares. We feel isolated, but are not.

Sheldon Kopp:

“Love is being open to experience the anguish of another person’s suffering…the willingness to live with the helpless knowing that we can do nothing to save the other from the pain.”

Getting Back to Normal

It was two years after my daughter’s death before my breathing returned to normal. Exhausted, in shock, psychologically confused, vision obscured, normal interaction impaired, I went about activity by rote. Friends, awkward, kept their distance. At times, I’d kept a busier than usual schedule, perhaps for the sense that there was something which continued to give life a sense of purpose. Some days I could barely function. The earlier story about walking along the New York sidewalk? The loss of my daughter is the experience of colliding with an immovable object.

Sharing my story is an idea that came only in its own good time, and still seems impossibly difficult. Time passed. I could talk about Ali without weeping. But I didn’t know where to start the story. I remember admitting to a high school teacher I was having trouble writing a paper. She said, “Just start at the beginning and write until you come to the end.” That was little help then or now. The ending is stark and abrupt. The beginning remains elusive.

Not long before her death, my daughter made me a dream catcher. People describe its purpose as allowing pleasant dreams through, stopping unpleasant ones. I remember an early afternoon, a breeze through the windows, sunlight through leaves of the tree spread about in speckled soft arrangements on the floor and walls. I sat, eyes unfocused, watching the dream catcher, as if I expected to see her fingers tying knots around the last feathers and beads. The experience is like hearing a plane on its landing path descent into Honolulu, and saying aloud to my daughter (who has been away long enough), “I’ll bet you’re not on that one, either.”

Her dream catcher hangs in front of my louvered closet door. Top and bottom shelves look like I’m determined to see how much they’ll hold before collapsing. The accumulation of papers, letters, pictures, books, file folders, old slides, boxes are a mix of a white elephant sale, a flea market, a not-quite-antiques auction. Of course, as each item joined the collection, it was indispensably meaningful.

Telling My Story

That afternoon, I remembered. Wedged among these memories were treasures—copies of letters, through the years, my daughter and I exchanged. I thought: perhaps I can use these letters to tell my story. So it began. I took my letters from the shelves, read them, alternately laughing, weeping, wondering, remarking at the events and emotions in each letter. Randomly, I chose one, then another, and the next. I began to read and make slight edits in the letters. The process was manageable, satisfying, and spared me the pressure of a deadline. There’s a happy-sad quality to sharing the correspondence with others. The letters elicit responses without difficulty. Emotions and experiences behind each exchange, laughter about an event remembered, are still “like yesterday.” But inescapably, the letters are a solemn reminder. These events, this life, is unrepeatable. My daughter is no longer living. The laughter I hear is in my head, not from her in the next room or over the telephone.

After rewriting each letter, I’d wonder the story’s beginnings. Every few letters resulted in changes in the introduction. It doesn’t seem possible, no matter how easy my high school teacher suggested it was, “just to begin at the beginning.” I suppose one reason was because the end of her life brought an emotional collapse. I don’t expect that to change soon. Time has passed. It’s possible to survive. But the collision with the immovable object occurred, and the hollow metal pole still vibrates.

About the Author

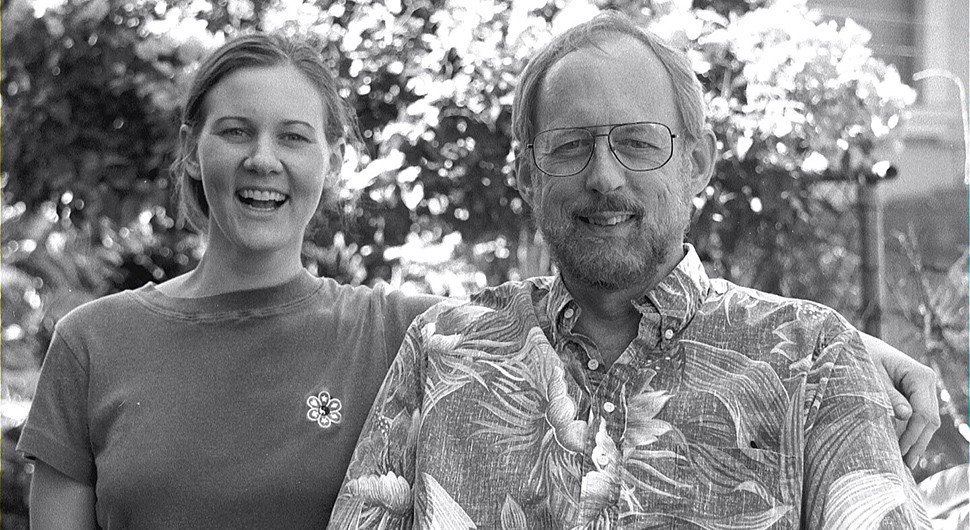

Raised in New England and educated in the Northeast, Midwest, Japan, and Hawaii, Joel has been a long time resident of the Islands. After serving as a high school and college teacher and administrator, Joel later became an employee benefits specialist and insurance company marketing vice president. Since 1990, he’s provided consulting services (employee benefits, group insurance, human resource issues, and education) to individuals, schools and corporate clients. The focus of his community service is on organizations representing people with disabilities and their families and, recently, in gathering people interested in discussing end-of-life issues. Joel’s daughter Alissa died at the age of 32.

No comments.