To commemorate the 20th anniversary of the implementation of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, we are featuring stories of those who in 1997 campaigned against the repeal of the law adopted by Oregon voters 3 years before and who continue to advocate for assisted dying laws nationwide. Today we are featuring Nora Miller, a Death with Dignity advocate in Portland, Oregon. In 1999, Miller’s husband, Rick, used the Oregon law to hasten his death.

Other installments in the series:

- 20 Years of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act

- “A Better Way”: George Eighmey’s Journey Toward Death with Dignity Nationwide

- “We Never Gave Up”: Geoff Sugerman on Campaigning for Death with Dignity

- From the Archives, 1997: In Letters to Lawmakers, Oregonians Voice Support for Death with Dignity

- “A Last Loving Gift”: Nora Miller on Grief, Advocacy, and the Right to a Dignified Death

- “Everyone Should Have This Option”: Jan Rowe on her Family’s Commitment to Death with Dignity”

- “We Have to Be Part of the Debate:” Ann Jackson on the Role of Hospice in the Death with Dignity Movement

- “What Brittany Asked Us to Do”: Deborah Ziegler’s Advocacy for Death with Dignity Honors a Promise to Her Daughter

*

When I meet with Nora Miller in early September, she has just begun unpacking from her move back to her Portland, Oregon from Tucson, Arizona, coming home to be near her son and his new wife. The living room of her new home is bare save for two large moving boxes, and we sit in folding camp chairs, a large box between us serving as a table.

As we settle in for our interview, Nora clears her throat, looks up at the ceiling, and begins to tell me about her husband, Rick, who in 1999 used the Oregon Death with Dignity Act to end his life after several months with cancer.

His decision, Nora says, was in keeping with his lifelong pattern of “swimming against the stream….He really didn’t go along with the rest of the world on a lot of issues. That’s what attracted me to him: that he was so different and independent.”

Nora Miller with her husband, Rick, on their wedding day.

Rick loved being outside and relished the times when he could escape to the woods on his motorcycle. Nora remembers one of many times Rick went on a solo camping trip; “it pleased him extremely that he was probably the only human within 20 square miles!”

In early 1999 Rick developed a cough that wouldn’t go away. “The diagnosis of metastatic terminal lung cancer in April left no room for doubt or hope for something less final,” Nora recalls. “His first words were, ‘Now we are going to Alaska.’” (Alas, they never made it.) His next words were, “I will be using the Oregon law”—the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, passed by voters in 1994 and enacted in 1997 after a lengthy court battle and an unsuccessful attempt to repeal it.

After a summer of experimental treatments—there was no treatment known to be effective—he was no better. “Rick told me he thought he’d be a lot sicker when he’d be making the decision to use the prescription,” Nora says. “He was, in fact, a lot sicker than he thought. He was having trouble with his voice and with swallowing. He often lost words or used them seemingly at random. He woke up with blinding headaches from a growing brain tumor, but the medicine to control the headaches made him emotional and weepy. He couldn’t walk on his own. He’d become emaciated.”

At the time Rick made his decision, the Oregon law had been in effect for just over a year.

“Not everybody at that time even knew about this law…except for the fact that it was the result of a very controversial vote,” Nora says. “Even his oncologist had never gotten a request before, which was pretty interesting.”

Rick was a deeply private person and had no interest in making headlines or engendering sympathy. “He just didn’t want anybody to know about it, it was nobody’s business but ours,” Nora says.

Nora was ready to help her husband die. There was just one problem: “We didn’t know anything about how the law worked.”

She contacted George Eighmey, Death with Dignity National Center’s current Board chair and former Oregon state representative, who at the time was president of Compassion in Dying of Oregon (CIDO). He worked with terminally ill patients and their loved ones to navigate the logistics of the law and provided emotional support to those facing death and those who would survive them.

“He sketched out how things were going go, what to look for, and how to handle things,” Nora says. “But he never said more than what I could deal with at any given time. He was amazing.”

By mid-September 1999, the doctor suggested it was time for hospice. Rick was able to stay at home. Later that month, Rick made his first oral request under the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, followed by a written request, and the final verbal request in late October.

Nora is grateful that Rick’s oncologist was receptive to his request despite never having written a prescription under the law.

“He was very open-minded and supportive about it,” Nora says, “and very frank, which I think even now is really hard for some doctors.”

She remembers traveling to a pharmacy 15 miles south of Portland to pick up the medication. At the time, the pharmacy was the only one in the state that would fill prescriptions in accordance with the law. When she brought it home to Rick, he was visibly relieved.

“It made all the difference to him to have it,” Nora says. “He still was anxious and uncertain about where things were going, but he definitely wasn’t anxious about the end.”

Unlike some patients who have used Death with Dignity laws to end their lives, Rick had not chosen a specific day to die, nor had he planned any sort of ceremony or event to bring together loved ones for one last goodbye.

“We didn’t have music, we didn’t have a circle of friends around…none of that happened,” Nora says.” His sister had just been to visit, so he was able to say goodbye. That evening, he just said, “get the applesauce”—into which they would mix the bitter-tasting medicine—”it’s time.”

“I challenged his intention,” she adds. “I told him he could sleep on it, decide the next day. He said, “no, I’m done.” He was sure. He was calmer than he’d been in weeks, almost jovial, relieved.”

Rick took the medication late on November 9th, and died on November 10, 1999. His wife and son and a dear friend were with him to the end.

“Despite the devastation, I had the consolation that it was his choice and that it made a difference to him,” Nora says. “And that I think was so important. It wasn’t his choice to die. He most definitely did not want to die. He loved his life! But given that dying was no longer a matter of choice anymore, he made it his choice to die at that moment, in that way. And we chose to help him do that.”

“This was a last loving gift we gave each other. I wanted nothing more than to make it possible for him.”

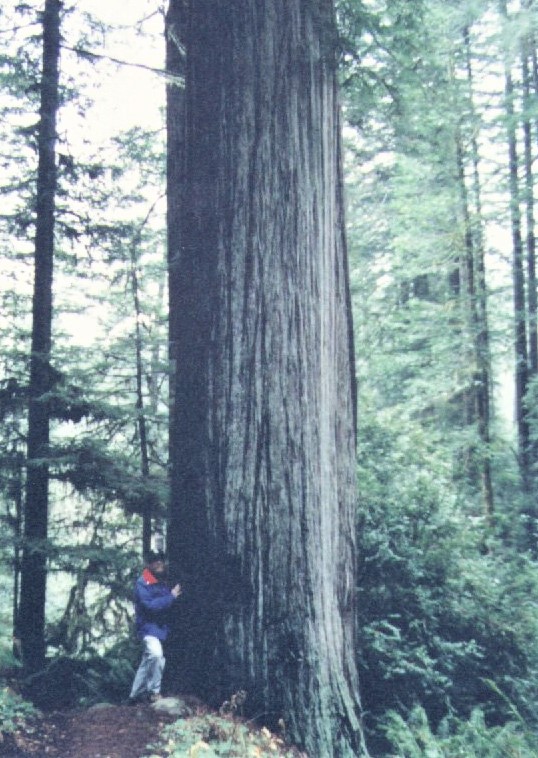

Rick Miller, lifelong nature lover and literal tree hugger.

The peace and painlessness that characterized Rick’s death stood in stark contrast to the agonizing struggle Nora’s mother and sister endured. Both of them died of cancer following invasive operations and difficult declines into helplessness.

For every single person who is dying, Death with Dignity means having the right to continue to be the person they’ve always been.

Her mother “wanted to go much sooner than she did,” Nora says. “She had emphysema, so breathing was hard, and her doctor talked her into getting her heart valve replaced so she would at least gain back a couple of years of life.”

When her mother awoke following her operation, she was in even more pain and was distressed by the additional trauma to her body.

“It became clear to us that she thought she would die on the operating table,” Nora says, “and that’s what she was hoping for. She said, “you should have just let me die!”

“It was a terrible death, partly because it was so long and drawn out, but also because there was no point at which anyone could say, “you know, dear, you’re dying and how do you want this to go, and what can we do to make this better?”

“It’s just not fair to not give people that,” Nora says. “They may not want to hear it, but that’s not a good enough reason not to tell them.”

Nora’s sister, Martha, who died in 2002, found out she had esophageal cancer after Nora flagged down a nurse in the emergency room where they had been waiting for hours on MRI results.

“Martha was lying on this stretcher in the hall,” Nora says. “I grabbed a nurse and said, we’re exhausted, she’s exhausted, can we go? And she said, oh, you’re the esophageal cancer with metastasis in the lungs and liver? And we both went…” Nora’s eyes widen; her jaw drops.

“Martha didn’t even get the courtesy of “you have cancer.” She just got, “oh, you’re the case.” Nora saw it as dehumanizing and a textbook example of how many medical professionals were, and in some cases, still are, unequipped to discuss issues of death and dying with their patients.

“The whole thrust of medical training up until the last 20 years or so has been exclusively, we don’t talk about death, we don’t think about death, we fight death at all times, and death is failure,” Nora says. “Fortunately, doctors are getting past that. They know they don’t want to have the kind of treatment they feel compelled to impose on other people.”

“But I think there’s also a problem in the general populace not wanting to talk about it,” Nora adds.

Indeed, despite the increased dialogue around end-of-life issues catalyzed by Brittany Maynard’s story, advocates from states as varied as Texas, Ohio, and Maine still encounter a culture of silence around death and dying. Fortunately, through their efforts and the continued commitment of people like Nora, there are a growing number of opportunities to speak out and bring conversations about death out of the shadows and into the mainstream.

“I think the best thing that’s come out of the Oregon law, not just in Oregon but everywhere, is how it’s opened the doors to people actually talking about this,” Nora says, citing the worldwide Death Cafe movement in which people come together to “eat cake, drink tea, and discuss death.” Such initiatives would have provided her comfort and solidarity she lacked after her loved ones died.

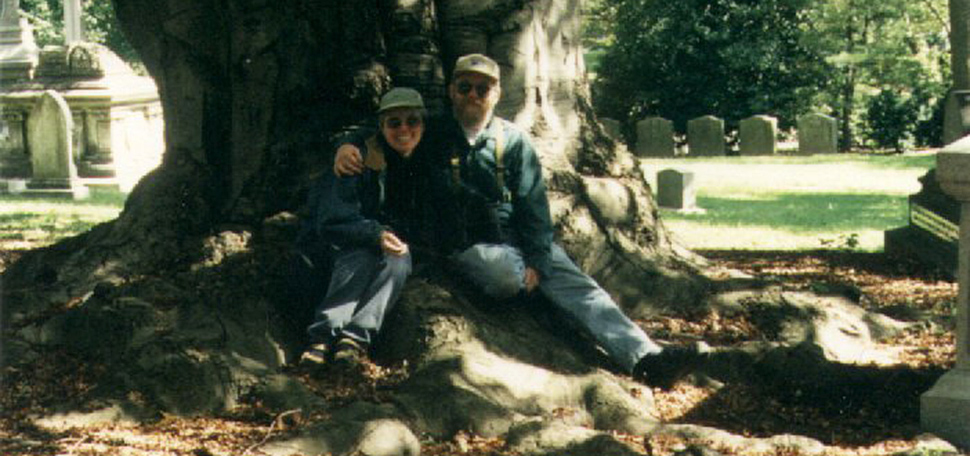

Nora and Rick Miller

“I didn’t tell many people about how Rick actually died for quite a long time,” Nora says—specifically, that he used medication prescribed by a doctor to hasten his own death.

“I knew there were people in my office, for example, that wouldn’t handle it well at all. Nobody knew people who did this.” She shared her grief with close friends, and sought a counselor who had some experience with the law.

“But now I tell people all the time, you have to talk to somebody. You have to move from mystery to history. Getting the grief out of your heart and into your head makes it all more manageable.”

Nearly 20 years after Rick’s passing, Nora says she has no regrets about helping Rick to achieve the dignified death he sought.

“I’ve never once regretted it,” she says. “I’ve often replayed those last weeks, recalling moments where I could’ve or should’ve done something differently. But I always understood that I did what Rick wanted, and to have done anything different would’ve made the process about me and not about him. It was his life and it was his death—he needed the right to decide how it would happen.

“For every single person who is dying, Death with Dignity means having the right to continue to be the person they’ve always been.”

No comments.