By Valerie Lovelace

Val is the executive director of It’s My Death, our partner organization in Maine which teaches “others how to be with dying, how to speak and listen to one another, and how to go on even when afraid.” She is an inter-faith minister, a hospice volunteer, a artist, a homeopathic practitioner, a Reiki Master, a U.S. Navy veteran, a trained EMT, and the parent of three adult children.

This guest article first appeared in It’s My Death’s email newsletter on February 16, 2016. The subheadings and links are ours.

Read our open call for guest writers →

*

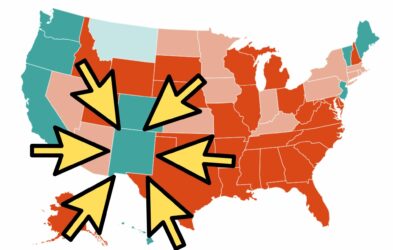

Across the world, the most controversial social, political, and ethical conversation is medical aid in dying, commonly referred to as Death with Dignity. The push towards visibility for the ways we die, personal ownership of that process, and the need to expand care to include a Death with Dignity option represents the desires of nearly 70 percent of polled populations in the United States.

The Physician-Assisted Dying Conversation

On February 3 in New Hampshire, an elderly man with colon cancer asked presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton for her thoughts on medical aid in dying. She was caught off guard. Her hesitant reply:

“We need to have a conversation in this country.”

The fact is, we’ve been having the conversation in this country for a long time. Even before 1994, when Oregon’s Death with Dignity law was first passed and immediately blocked by injunction. Enacted in 1997, Oregon’s Death with Dignity law stands the tests of time and scrutiny, and continues to be held up worldwide as the model for a safe aid-in-dying option.

Had Maine’s Death with Dignity bill passed in 2015, it would have permitted a physician to write an end-of-life prescription for a competent, terminally ill adult. The bill outlined a formal, safeguarded process by which the process could take place, clearly stating only the patient could choose when or whether to take the medication as death became imminent—medication that the patient must be capable of self-administering.

Opposition to Physician-Assisted Dying Legislation in Maine

When Senator Roger Katz’s bill, LD 1270, went through the legislature, two groups involved in disability rights forcefully opposed it.

Disability rights groups asserted that passage of LD 1270 would surely mean a slippery slope to future unacceptable risks for those less able to protect themselves. This is not a unique stand for disability rights groups. The question is, “Why is this their position?”

There is no legal foundation for it. There are no court cases nor pending charges of any kind for abuse or coercion of elderly, poor, or disabled persons, despite what opposition groups persistently contend. Not a single precedent exists.

There are no court cases nor pending charges of any kind for abuse or coercion of elderly, poor, or disabled persons, despite what opposition groups persistently contend.

Only qualified competent terminally ill adults can ask for and use an end-of-life prescription where it is legal to do so in the United States.

Disability rights groups do really terrific work in this state. Yet a terminally ill person in Maine is legally defined as a disabled person under the Maine Human Rights Act. As such, competent terminally ill persons desiring passage of legislation in Maine ought to be supported in their quest for a safe law that may prevent their suffering at the end.

Let’s Wait?

This is and has been a part of our conversations about dying in Maine since 1995, when Maine’s legislature first attempted passage of a law much like Oregon’s. The argument then was, “Let’s wait to ensure that we are delivering high quality end-of-life care to everyone in Maine.” Last year, LD 1270 failed by one Senate vote. The argument? A different version of “Let’s wait to ensure that we are delivering high quality end of life care to everyone in Maine.”

An end-of-life prescription does not replace hospice or palliative care. It adds to those services in a way that is meaningful for the patient who desires it.

Facts are facts. An end-of-life prescription does not replace hospice or palliative care. It adds to those services in a way that is meaningful for the patient who desires it. Over 90 percent of those who die in Oregon using a prescription are also enrolled in and receiving hospice care. The truth is, passage of the law in Oregon promoted rapid improvements for and access to end-of-life care in every county of that state, even the most rural.

Ask the Questions

We are having the conversation about aid-in-dying in Maine, and we have been since 1995 when the legislature first attempted to pass a law like Oregon’s. Not everyone wants to talk about it, not everyone wants to understand it, and many try to avoid the topic. That won’t make it go away.

Dying people should have a right to access what they need at the end of their lives in a way that is both meaningful and comforting to them. No medical, religious, political, or other special interest establishment should be able to insist that people must die according to the current paradigm of care being offered.

If we want more options when we’re dying, we have to be like the elderly man who asked Clinton about her thoughts on the issue. And then be prepared to educate and advocate.

Where do your representatives stand on this issue? Where does your physician stand on this issue? Your clergy? Your family?

It’s time to start asking.

Featured image by cranberries.

No comments.