Update: California’s physician-assisted dying law, ABX2-15 (AB-15), the End of Life Option Act, took effect on June 9, 2016.

By Christopher Stookey, MD

The California End of Life Option Act (ABX2-15), signed into law on October 5, 2015, is a victory for Death With Dignity advocates. When the law goes into effect sometime in 2016, California will become the fifth state—along with Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and Montana—to allow doctor-assisted dying. Adult individuals with a terminal illness will be allowed to request, receive, and to self-administer aid-in-dying medication.

As someone who is sympathetic to Death With Dignity movement, I applaud the passage of ABX2-15. However, as much as I approve of this new law, there are ways in which I wish the law had been even stronger. I’ll explain why I feel this way using the example of my own father’s death.

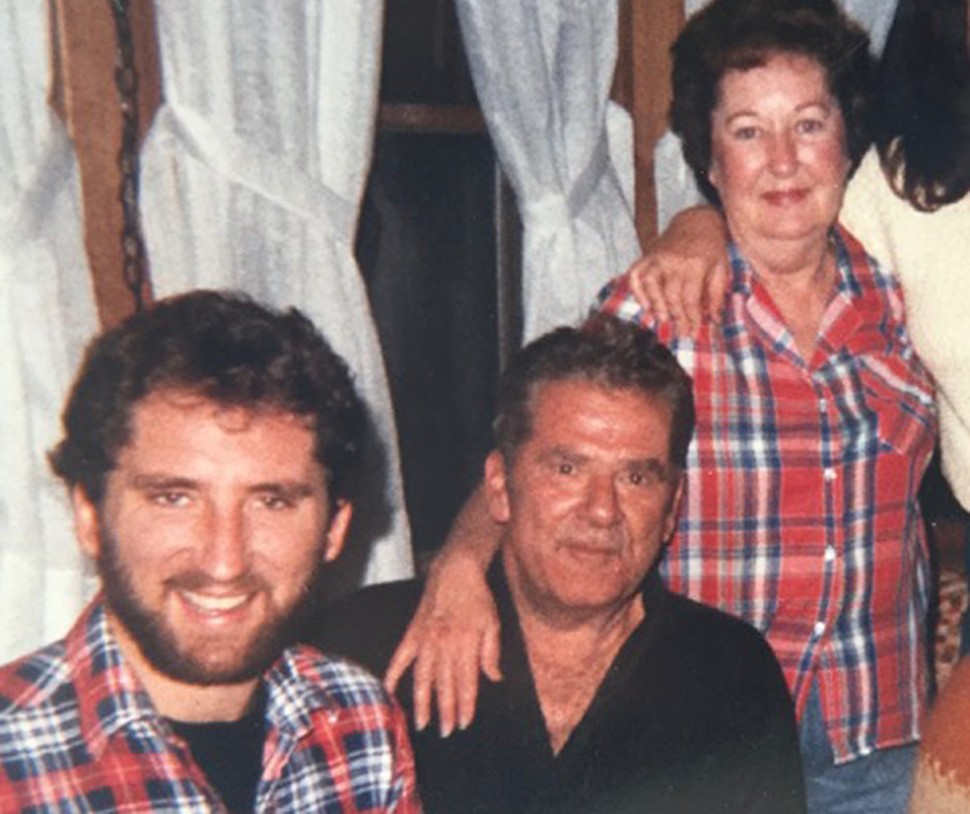

Bringing Dad Home to Die

In 2008, at age 83, my dad suffered a massive stroke. It left him conscious yet unable to talk and communicate, unable to swallow, and almost completely paralyzed (he still had a small bit of strength in his left arm). His doctors determined that there was no chance for recovery. My father would never walk, talk, or swallow food again. The social worker on the case encouraged us to put Dad in a nursing home. A gastric feeding tube could be put in, and he could be fed and kept alive that way. Indefinitely.

My mother, my sister, and I knew this is not what Dad would want. He had been very clear about his end-of-life wishes. Long before the stroke, he had told us—more than once—that he would rather die than be put in a nursing home.

He felt this way for two reasons:

- He was an obsessively active man who believed every day should be marked by some accomplishment. A life confined to a hospital bed would be a living hell for him.

- His mother had died a slow, agonizing death due to cancer. Dad never wanted to go through what had happened to his mom. I recall once during dinner when Dad talked bluntly to me about his mother’s suffering. Looking me squarely in the eyes, he said: “If I ever get like that, I want you to give me hemlock.”

Hemlock. It was his code word for assisted suicide. And I knew he was serious.

After the stroke, Dad could no longer express his wishes. However, his advance directive gave us guidance. “It is my desire that measures not be taken to prolong my life if the results of such efforts will not leave me in a condition where I will be able to enjoy a reasonable quality of life.”

Based on the directive and everything we knew about Dad, we decided to forgo the nursing home and to bring him home. We would also forgo the feeding tube. No food, no water, no IVs. In other words, we were bringing Dad home to die. We knew this is what he wanted.

I also knew that, if my father could talk, he would ask for the “hemlock” he had talked about that evening over dinner. What was the point of slowly dying over several days due to starvation and dehydration when a medication could accomplish the same thing more quickly and comfortably?

Unfortunately, as a resident of California before the passage of ABX2-15, “hemlock” was not an option for my father. However, even if he’d had his stroke after the passage of the law, assisted death would still not have been available to him. For one thing, the law specifies that a person seeking a prescription for end-of-life assistance must make two requests for the prescription, 15 days apart. Owing to the stroke, my father could not communicate; there was no way he could make such a request. In addition, the law requires that a patient be able to take the prescribed life-ending medication on his or her own. My dad was nearly completely paralyzed, and he couldn’t swallow. He couldn’t possibly have taken the medication on his own.

How to Strengthen the California End of Life Option Act

I believe ABX2-15 could be strengthened by adding a provision that would allow assisted dying in end-of-life situations such as my father faced. I’m sure my dad would have altered his advance directive to reflect the “hemlock” option if it had been available to him.

No doubt, there will be those who feel such a provision is unnecessary. Many in the hospice community argue that the way my dad died (by VSED, or Voluntary Stopping of Eating and Drinking) is a relatively gentle way to day. Death-hastening medication is not needed. As dehydration sets in, they say, the body releases certain chemicals (esters and ketones) that have the effect of dulling the senses. These chemicals act as an anesthetic, and, as a result, the patient dying of dehydration feels little pain or discomfort.

I’m not so sure about this. I can’t help but believe there must be some discomfort associated with dying by dehydration. Although my father was paralyzed, he was fully conscious. Indeed, he started to exhibit signs of agitation and distress (rapid breathing, moving his left arm, grimacing) about 48 hours after we stopped food and water. The signs of distress continued over the next days despite increasing doses of morphine and Ativan (a sedative).

It took Dad seven days to die. During the last 24 hours, he began to lose consciousness, and he finally seemed to reach a point that was beyond pain and discomfort. Nevertheless, I will forever believe that he suffered unnecessarily for the several days it took him to reach that point.

My mother and I were both at the bedside when he died. He took one final breath, then he was still. I wish I could say he looked at peace in death, but he did not. There was a disturbing look on his face with the sunken eyes and the half-open mouth outlined by blue lips. To me, it was a look of perplexity and bewilderment. To me, it was a look that said: “Where, Son—where, my doctor son—was my hemlock?”

About the Author

Chris is an emergency physician in Laguna Beach, California. He is the author of Do Go Gentle: Bringing My Father Home to Die With Dignity After a Devastating Stroke, a memoir documenting his experience witnessing his father’s death. A selection from the book appeared on our website last year as Chris’s personal story.

This guest article reflects the author’s views only; we neither endorse or disapprove of its content.

Read our open call for guest writers →

One comment.

P

Before my mother being diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer, I never gave much thought to the slow painful process of dying. We were relieved that the end of life act passed in California that same year. But now that is actually effective and my mom has asked her physicians, that relief has turned to dread. It seems like hospitals are not ready to deal with requests and give you the same answers as before the Act existed.

Comments are closed.